【連載】これから演劇を始める人のための演劇入門 ENTRANCE=EXIT, FOR STARTING THEATER―第4場 アジアの共通言語はどのようにして構築可能か?<前編> How can we create a common language in Asia?<Part 1>

これから演劇

2019.06.6

*藤原ちからによる新連載。コンセプトについてはこちらをご覧ください。

*English is bellow the picture, you can translate into your language easily.

* * *

【前編】

この一ヶ月ほど、香港、シンガポール、マニラ(フィリピン)を回ってきました。この3つの都市にはいくつかの共通点があります。まず、超暑い……! そして英語が公用語のひとつであるということ。今回はこの「英語」について考えてみましょう。

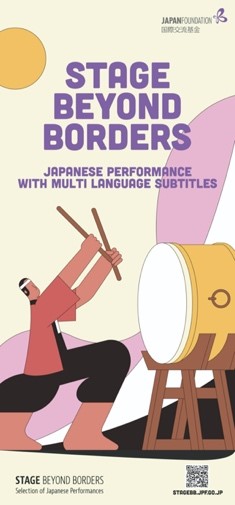

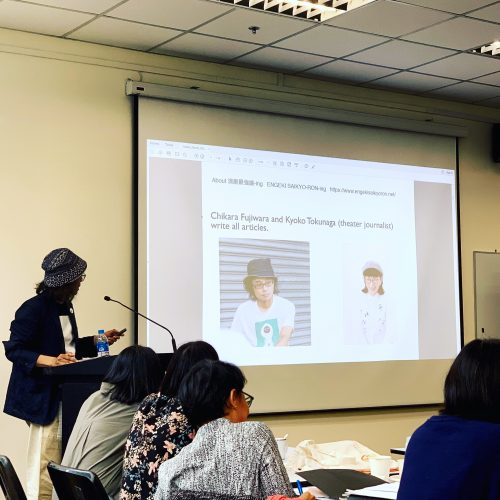

シンガポールでは、Asian Art Media Roundtable (AAMR) という国際会議に参加しました。東南アジアにフォーカスしたアートメディア・Arts Equaterが主催で、日本の国際交流基金アジアセンターもサポートしています。今回が第1回目の開催でしたが、2.5日間の会議は充実した内容となり、情報共有のファーストステップとしては大きな成果を挙げたのではないでしょうか。ここで当日の写真を見ることができます。

この連載の第2場に書いたように、舞台芸術に関する国際的なミーティングはすでにアジア各地で活発に行われています。その中でもこのシンガポールのAAMRは、アーティストやプロデューサーではなく、批評家やジャーナリストの集まりだという点で特殊でした。批評家たちの使う抽象的で、複雑で、早口な英語を理解するのはそう簡単なことではなく、英語力を向上させなければ……と痛感しました。しかし同時に、この言語についての困難を、参加者の英語力の問題のみに帰着させてはいけないとも感じました。アジア各地から集まった参加者全員が英語を流暢に喋る、という「理想的な」状況は到底想像できなかったからです。わたしの頭には次の問いが浮かびました。それは「アジアの共通言語はどのようにして構築可能か?」という問いです。

AAMRにおいてわたしは、このウェブサイト「演劇最強論-ing」についてプレゼンしましたが、そのセッションのQ&Aでも、言語の問題は大きなトピックになりました。批評家は言葉を使って何かしらの効果を呼び起こそうとする、いわば「言葉の魔術師」です。やはり自分がどのような言葉を使うかには敏感なのでしょう。

旧約聖書によれば、バベルの塔の崩壊以前には、人々は同一の言語を話していたとされています。もちろんこれは神話であり、架空の物語だと考えられます。それでも、共通言語をつくりたいという願いは、今も多くの人々の夢ではないでしょうか。19世紀末にユダヤ系ポーランド人のルドヴィコ・ザメンホフによって考案されたエスペラント語は、そんな夢の象徴だったのかもしれません。わたしはある文章(石原吉郎の「ペシミズムの勇気について」)を読んで、シベリアに抑留されていた日本人がエスペラント語で歌ったというエピソードに深い感銘を受けたことがあります。Mi preskau perdis esperon… あるいは日本の有名な漫画『ドラえもん』に登場する「ほんやくコンニャク」は、それを食べるだけであらゆる言語が理解できるようになるという夢のような道具でした。技術が進歩し、声や文字が別の言語へと瞬時に翻訳されるようになった現在、ドラえもんの世界はもうただの夢物語とは言い切れません。

しかしこの先どんなに技術や知恵が進歩したとしても、まったくズレを生まない完璧な翻訳が為されることはありえないでしょう。そして、誰にでも通じるような完璧な言語も登場しないでしょう。

【命題】完璧な言語は存在しない。

まずはこの命題を共通認識として出発したいと思います。

もちろん英語も完璧な言語ではありません。それでも英語が今のところビジネスや学問の世界で覇権を握っているのは事実です。第二次世界大戦後にアメリカ合衆国の存在が絶大なものになったことが大きな理由でしょうが、複雑な要因が絡み合ってこうなったはずです。アジア各地においては、それぞれの歴史的事情もあります。前述したように香港、シンガポール、マニラ(フィリピン)はいずれも英語を公用語としていて、それは植民地支配の歴史と濃密に関係しています(ちなみに、いずれの都市もかつて日本が占領していた時期があります)。各地の言語事情をここで詳細に分析することは不可能ですが、ごく初歩的な事実とわたしの所感だけ記してみます。

香港は1997年までイギリス領でした。香港島のバーなどに行くと西洋人の姿ばかり見かけますが、ローカルなエリアに入っていくと年配層で英語を話せる人はごくひと握りでしかありません。若い世代への英語教育は盛んで、返還後も、英語はキャリアップや国際競争力の確保のために必要とされているように見えます。そのためか若い人たち、特にアートに関わる人たちはとても流暢な英語を喋ります。しかしそれでもなお、彼らが精神的の拠り所は母語である広東語だと感じることがよくあります。

シンガポールもやはり歴史的にイギリスの影響が大きくありますが、英語の他に、マレー語、中国語(普通話)、タミル語が公用語とされています。しかし華人系の家庭ではそれぞれの出自によって普通話とは別の中国語が使われていることもあり、母方は福建語で、父方は客家語、という複雑なケースもあります。インド系の人々も全員がタミル語を話すわけではなく、複数のインド系の言語が混在しているようです。ちなみに国語は(マレーシアから独立したという経緯もあって)マレー語です。そうした複雑な言語環境にあって、英語は意思疎通の道具として「よりマシな」言語ではあるのかもしれません。独特な訛りを持つシングリッシュはそうして生まれたピジン言語(異言語間の意思疎通のために生まれた言語)なのでしょう。しかし政府の方針で、公共放送ではシングリッシュは原則禁止とされています。流暢な英語を喋りたいという欲望/束縛を、シンガポールの人々がどれだけ感じているかはわたしにはまだわかりません。ただ一般的には、状況を批判するよりも、状況に従うほうがラクではあります。たとえそれが誰かを排除するとしても……。わたしは劇場で非常に高速な英語でまくしたてられる会話劇を観て、残念ながらここにリトル・インディアの人たちが来ることはまずないだろうし、観客としても想定されていないのだと思わざるをえませんでした。

フィリピンはアメリカ合衆国の影響が大きく、公用語は英語とタガログ語です。アートに関係する人たちのほとんどは英語を喋りますが、それは彼らが高いレベルの教育を受けているからです。裕福な子女が入る学校では、「英語以外の言語を喋ると罰金」という厳しい規則を設けているところもあると聞きます。おそらくそれは英語を推奨するためのゲームなのでしょう。しかし貧富の差が激しいフィリピンにおいて、英語は誰にでも理解できる言語というわけではありません。アーティストたちにとっても、英語は彼らのほとばしる感情を表現するには不十分のようで、感情がノッてくるとすぐにタガログ語やタグリッシュ(タガログ語と英語のチャンポン)へと切り替わります。ただしタガログ語が母語であるとはかぎりません。異なるプロヴィンス(田舎)から集まっているマニラのアーティストたちの多くは、それぞれの母語を別に持っています。つまり3つの言語が話せるというのは珍しいことではありません。

香港、シンガポール、マニラの例を早足で挙げました。これらの都市では英語との結びつきが濃密であるだけでなく、ポリグロット(複数の言語を喋る人)も珍しくありません。しかし他のアジアの諸都市、特に東アジアでは、単一の言語が主流を占めているために、言語の多様性を生活の中で実感しにくいこともよくあります。日本がまさにそうであるように。

アジアには英語を喋らないアーティストもたくさんいます。批評家もそうです。わたしが知るかぎりでは、各国内において高い影響力を持つ批評家でも、英語を喋らないということは珍しくありません。批評家はインテリなのだから、流暢な英語を身につければ問題は解決する、という考え方もあるでしょう。しかし東アジアのように、日常的に多言語に触れる機会が少ない国に育った人にとって、英語の言論空間への参入は簡単なことではありません。ハンディキャップがあります。むしろ東アジアの批評家にとっては、中国語圏での議論を深めていくほうが彼らのキャリアを伸ばすかもしれません。仮にわたしが中国人で、マンダリンしか理解できないとします。中国本土、そして飛躍的にプレゼンスを高めつつある台湾ではマンダリンが通じますし、繁体字さえ読めれば香港やマカオでも文章を読解することができます。もしかしたらマレーシアやシンガポールの華人コミュニティにもアクセスできるかもしれません。不得意な英語の環境にアクセスするよりも、得意な中国語を使って活動する幅を広げていくほうが簡単で、かつ効果的でさえあるかもしれないのです。東アジアの批評家たちが今よりも英語を流暢に使いこなすという状況は、今後もおそらく見込めないとわたしは思います。では、どのような方向性を目指せばよいのでしょうか?

(後編につづく)

I’ve been to Hong Kong, Singapore and Manila (Philippines) for about this one month. These three cities have some things in common. First of all, it’s super hot…! And English is one of the official languages of them. This time, let’s think about this “English”.

In Singapore, I participated in an international conference called Asian Art Media Roundtable (AAMR). It was operated by Arts Equater which is an art media focusing on Southeast Asia, and the Japan Foundation Asia Center supported as well. This was the first held. The 2.5 days conference had become a fulfilling content, and it had made great achievements as the first step of sharing information. You can see the photos here.

As I wrote in the second article of this series, international meetings on performing arts are already held actively throughout Asia. Among them, AAMR in Singapore was unique because it was a gathering of critics or journalists, not of artists or producers. It was not so easy to understand the abstract, complex, fast-paced English of the critics, and I felt that I should improve my English ability… But at the same time, I also felt that this kind of difficulties about language should not be focused only on the participants’ English ability. I couldn’t imagine an “ideal” situation that the all participants from all over Asia spoke fluent in English. The following question arose in my mind; “How can we build a common language in Asia?”

At AAMR, I made a presentation about this website “Engeki Saikyo-ron-ing”, and even in the Q&A session, language problems became an important topic. Critic uses words to evoke some effects, like a “word magician.” They are sensitive to what kind of language they use.

According to the Old Testament, before the collapse of the Tower of Babel, people were speaking the same single language. Of course, this is a myth, and I can say it’s a fictional story. But this kind of desire to create a common language is still a dream for many people. Esperanto, conceived by the Jewish Polish Ludovico Zamenhof at the end of the 19th century, might be the symbol of such a dream. I red an essay and was deeply impressed by the episode that a Japanese sang in Esperanto at a Siberian Prison Camp. Mi preskau perdis esperon… Or “Honyaku konjac (Translation Gummy)”, which appears in the famous Japanese comic “Doraemon”, is a dream-like tool that you can understand all languages just by eating it. Now that technology has progressed, voices and letters can be instantly translated into another language. The Doraemon world is no longer just a dream story.

Anyway, no matter how advanced the technology or wisdom will be, there will be no perfect translation without any deviation. And also there will be no perfect language which is understood by anyone.

【Thesis】There is no perfect language.

At first I want to put this thesis as common recognition.

Of course, English is also not a perfect language. But so far it’s true that English holds the hegemony in the business and academic world. The big reason may be the existence of the USA after WWII, and Complex factors should have created this situation. In Asian countries, there are historical circumstances on each. As I mentioned above, Hong Kong, Singapore and Manila (Philippines) all have English as one of their official languages, which is closely related to the history of colonial rule. (Incidentally, the both cities had Japanese occupation era.) Although it’s impossible for me to analyze in detail the linguistic situation of each cities, I will write only the basic facts and my feelings.

Hong Kong was owned by UK until 1997. If you go to a bar in Hong Kong Island, you will see many Westerners, but if you go into a local area, there are only a few elderly people who can speak English. English education for young generation is popular, and even after the Transfer of the sovereignty, English seems to be needed for their career and international competitiveness. That is why young people speak very fluent English, especially art people. Nevertheless, I often feel that their spiritual language is their mother tongue, Cantonese.

Singapore is also historically heavily influenced by UK. In addition to English, Malay, Mandarin, and Tamil are considered official languages. Further,, some of Chinese families use a different Chinese language depending on their origins, and there may be complicated cases in which the maternal side is Fujian / the paternal side is Hakka and so on. Not all Indians speak Tamil, and it seems that several Indian languages are spoken. The national language is Malay (probably due to its independence from Malaysia). In such a complex language environment, English may be a “more better” language as a communication tool. Singlish may be a Pidgin language that was born like that with a unique indignation. However, according to the government’s policy, Singlish is generally prohibited in public broadcasting. I still don’t know how much people in Singapore feel for the desire / restraint to speak fluent English. In general, it’s easier to follow the situation than to criticize the situation. Even if it displace someone… I saw a very fast English-speaking conversation play at a theater, and unfortunately people living in Little Indian community rarely come here, and I felt that they are not supposed to be audiences.

The Philippines is heavily influenced by USA, and the official languages are English and Tagalog. Most of the people related to art speak English because they have a high level of education. I heard an episode that a school having rich children has strict a rule that say, “If you speak without English, you should pay a penalty.” Perhaps that’s just a game to encourage English ability. Anyway, in the Philippines, where the gap between rich and poor is severe, English is not a language that anyone can understand. For artists too, English seems to be inadequate to express their emotional feelings, and as soon as the emotions come in, they switch to Tagalog or Taglish. And, Tagalog may not be their mother tongues. Many artists living in Manila from different provinces have different mother tongues. In other words, it’s common to speak three languages.

I’ve listed quickly examples of Hong Kong, Singapore and Manila. In these cities there are strong connection to English, and polyglots are not uncommon. However, in other Asian cities, especially in East Asia, because a single language often predominates, it’s difficult to feel the diversity of languages in their lives. Like Japan.

In Asia, there are many artists who don’t speak English. Critics too. As far as I know, even if the critics are highly influential in each country, it’s normal that they don’t speak English. You might consider that they can solve the problem by getting fluent English because they are intelligentsia. However, for those who have grown up in an environment where they don’t have access to many languages on their daily life, entry into the English discourse world is not an easy task. There is a handicap. Rather, for East Asian critics, deepening their discussions in the Chinese-speaking world may grow up their career. Let’s assume that I am a Chinese and can only understand Mandarin. In Mainland China, and Taiwan which is rapidly increasing its presence, I can communicate in Mandarin. And if I try to read traditional Chinese characters, I can read texts in Hong Kong and Macao as well. I may also have access to the Chinese communities in Malaysia or Singapore. It may be easier and more effective to extend the range of activities using Chinese rather than using poor English. I can not anticipate the situation where critics in East Asia use English more fluently than now. So what direction should we aim for?

(to be continued to Part 2…)